Raising the Bar for Racial Equality

By Cathy Miehm, Originally Published on CLAC

There is more work that we must do to ensure diversity, equity, and inclusion in our workplaces

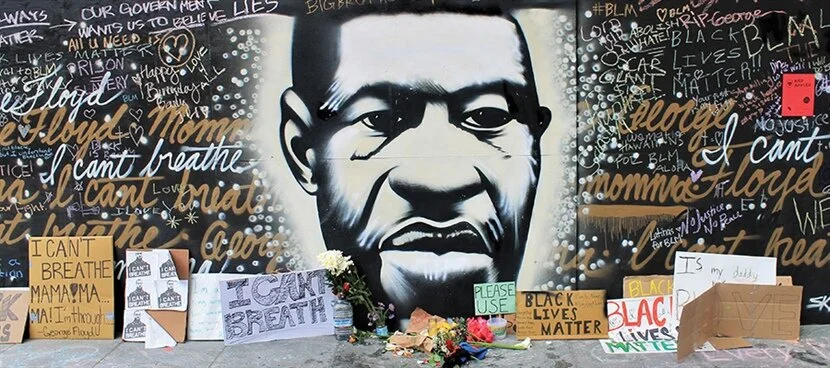

In May 2020, George Floyd a Black American, died at the hands of police during a violent arrest in Minneapolis. A white officer is now facing murder charges.

The Black Lives Matter protests, spurred by this and multiple other police killings in the US in recent years, have put the issue of racial injustice front and centre in communities and workplaces around the globe.

“George Floyd wasn’t the first death or act of police violence that we were able to watch on TV, but it was the one that made everyone start talking,” says Colleen James, principal consultant and CEO at Divonify, a Kitchener, Ontario-based equity and inclusion consulting company. She was recently recognized by the Canada International Black Women Event as one of the country’s top 100 Black women to watch in 2020.

“As someone who has worked in an office, I can tell you that any other time this happened, there was never any discussion about it. But by ignoring it, you’re really ignoring the greater problem. And that speaks to the whole idea of privilege. Someone is privileged to be able to turn it all off and say, ‘I don’t want to watch the news,’ but the issues are still happening.”

For the first time since, the US civil rights movement, a very bright light is shining on the age-old problem of racism, and it has spurred a lot of soul-searching. Workplaces, as well as individuals, are looking within and trying to root out both obvious and subtle biases.

In the days following the shocking death of George Floyd, scores of businesses and organizations, including CLAC, issued public statements denouncing racism. These are a good first step for workplaces committing to greater equity and inclusion, but there is a long road between where we are and lasting change.

Unions and their members can play a critical role in bringing racial justice to the workplace. They are in a strong position to advocate for change.

CLAC takes that responsibility seriously and is committed to making our work communities safer and more equitable for people of all social and ethnic identities. We must all listen to coworkers experiencing discrimination, be accountable for our own roles in perpetuating it, and speak out when racism happens.

“If it is happening to one person, it is usually happening to somebody else,” says Colleen. “Unions create a space where people can collectively come together. They have a union representative they can turn to.

“I am a firm believer, though, that to create that safe place for employees to come together, it needs to be embedded within the organization. They need to ensure that the grassroots, shop-floor initiative has a place to go that’s actually authentic, where employees feel that they will be heard and won’t be reprimanded.”

It’s not just overt acts of racismthat perpetuate discrimination in the workplace. The notion of unconscious bias—implicit prejudice against certain groups leading to unintentional different treatment—now forms part of the mainstream understanding of discrimination. Canadian courts and tribunals recognize unconscious bias as a form of systemic racism.

Employers must recognize microaggressions and how they cause discrimination. Conduct which may have been previously viewed as innocuous may no longer be deemed acceptable by courts. Discrimination does not have to be intentional for it to constitute a violation of human rights legislation.

Ultimately, complaints about racism in the workplace are not necessarily going to arise only from single, isolated incidents of overt racism. They can also stem from a culture that creates a space for microaggressions and unconscious bias over a sustained period of time.

An employer’s failure to adequately address systemic racism may result in liability in three areas:

Human rights – Federal and provincial human rights legislation prohibits discrimination in employment on the basis of race, colour, ethnic origin, and place of origin. The Supreme Court of Canada has confirmed that systemic discrimination is a violation of human rights legislation. An employee may seek damages under such legislation from employers who allow systemic discrimination to pervade the workplace.

Occupational health and safety – Most jurisdictions have legislation that prohibits workplace harassment. A poisoned work environment constitutes workplace harassment and may arise from hostility toward racialized workers. An employer may be liable under human rights legislation or under occupational health and safety and/or workers compensation legislation.

Common law – A poisoned work environment may entitle an employee to resign, claim constructive dismissal, and seek wrongful dismissal damages against the employer. An employee may also claim aggravated or punitive damages related to discrimination in employment.

In a healthy workplace, the employer, union, and workers come together to improve both diversity and equity. A first step is to acknowledge that workplace racism exists in myriad forms, many of them institutional. Employers and workers should be asking the following four questions:

Is there prejudice or bias?

Is there stereotyping?

Have there been incidents of racial profiling?

Are there subtle forms of racial discrimination, such as failing to hire, train, mentor, or promote Black, Indigenous, or persons of colour?

In all of these conversations, it’s important that racialized employees have a voice, says Colleen. That may seem obvious, but workers often encounter barriers that may be invisible to their white colleagues. For example, the way some companies recruit workers for committees may unintentionally be closing the door to people with the most at stake.

“There can be a barrier if you are asking about education right away, if you’re asking for employment history, if you’re asking what other committees they have been on before,” says Colleen. “When we’re trying to engage communities we haven’t engaged with in the past, it’s important to ask about their personal stake—why they’re passionate about serving on this committee.”

Organizations that want to evolve must examine their own “standards and the status quo that was set up in the past and understand that they need to change,” she adds.

Change must also take place in personal interactions. White people who see themselves as progressive may, in trying to appear not racist, avoid the topic of race with their employees and colleagues of colour.

Dr. Robert Livingston, a Harvard University lecturer and expert in diversity, leadership, and social justice, addressed these people in an article he wrote for a recent issue of Harvard Business Review.

“Workplace discrimination often comes from well-educated, well-intentioned, open-minded, kind-hearted people who are just floating along, severely underestimating the tug of the prevailing current on their actions, positions, and outcomes,” he writes. “Anti-racism requires swimming against that current, like a salmon making its way upstream. It demands much more effort, courage, and determination than simply going with the flow.”

Colleen would like to see more people initiate conversations with coworkers of colour, and listen when they share personal experiences.

“I think it often comes down to really understanding who’s working with you and seeing through a different lens,” she says. “Consider what it’s like to feel like your life is literally on the line every time you come in contact with the police.”

Canadians often Mollify themselves with the myth that racism here isn’t nearly as overt, systemic, or embedded in our history as racism in America. But despite the impact of grassroots movements such as Black Lives Matter, racism and discrimination are still part of many Canadians’ lives, especially in the workplace.

A 2020 Morneau Shepell report found that more than 60 percent of Black Canadians have seen racial discrimination in their workplace. Another recent survey noted that almost 40 percent of visible minorities said that they either often or sometimes encounter discrimination at work.

Our First Nations still suffer the fallout from more than two centuries of discrimination, neglect, and abuse. To this day, some Indigenous communities struggle to survive without a clean, safe supply of drinking water.

Indigenous Canadians can feel especially singled out. A 2019 survey conducted by the Environics Institute found that more than half of Indigenous Canadians have experienced ongoing discrimination. Nearly a third agreed that they were treated less fairly than their white coworkers.

Discrimination not only translates to lost opportunities and a hostile work environment but to lost income as well. In the US, Black and Latinx women experience this effect the most. It is estimated that over a 40-year career, women in these demographics will lose out on a million dollars—or more.

A 2020 survey found that 40 percent of male visible minorities working in Canada either somewhat or strongly disagreed with the statement that they are paid fairly for the work they do, compared to 28 percent of male nonvisible minorities. When looking at women, 40 percent of visible minorities disagreed, while 37 percent of white respondents felt the same.

Last November, A CBC Marketplace investigation of racism in the oilsands shed light on the difficult reality of being a person of colour in an industry dominated by white men. Marketplace interviewed several oilsands workers of colour about the culture in the sector. The types of discrimination they encountered included being denied overtime and advancement opportunities and being advised to change their names to something more “Western” to improve their chances of getting a permanent position. They also experienced difficulty moving from contract work to permanent positions, regardless of their qualifications.

Many workers said that racist comments from colleagues were common, but those comments were rarely reported to managers.

“Across the board, you just don’t complain about things,” said Sara Dorow, chair of the sociology department at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, who has studied the oilsands sector for more than a decade.

She recalled an example from a recent survey she conducted on mental health among oilsands workers. One worker, a South Asian man, said his response to slurs was to stay quiet. “I’m not there to make friends or solve racism,” he said. “I’m just there to collect a paycheque.” Unfortunately, none of these barriers is unique to the oil industry. In 2018, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives found that across Ontario, people of colour earn an average of 81 cents to every dollar white Canadians earn.

“These findings point to the need for Ontario to deal with the uncomfortable truth that its labour market is not equally welcoming to all immigrants, and that differences in immigrants’ outcomes are not based only on education levels and language skills, but also on racialization,” concluded a report titled Persistent Inequality: Ontario’s Colour-Coded Labour Market. It calls for “bold new policies to close the persistent gap between racialized and non-racialized men and women.”

“When we talk about immigration, people should understand that we’re all settlers in some capacity or another,” says Colleen. “I think it would be helpful if our schools would offer a more in-depth perspective of our history—not so much the European-centred, settler mindset. How many people know slavery existed here? Those are some of the stories and narratives that have not been told.”

If we can bring appreciation for these other experiences into our workplaces, then change is possible.

“The past year amplified everything,” says Colleen. “It’s made employers ask, what can we do better? Where are the gaps? Where have we dropped the ball, and what systemic barriers are present? Once you answer those questions, you can start creating an environment where everyone feels like they can freely discuss and start to solve issues of race.”

Sources: Harvard Business Review, MillerThomson, Global News, Environics Institute, Canadian Race Relations Foundation, CBC Marketplace, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives